Extension methods have been a core C# feature since version 3.0, enabling developers to add methods to types without modifying source code. With C# 14 and .NET 10, Microsoft introduces extension members—a powerful enhancement that extends beyond methods to include properties, operators, and static members.

This comprehensive guide explores how C# 14 extension members enable you to add mathematical operators to Point, create static factory properties for IEnumerable<T>, and organize extensions more elegantly than ever before.

What Are Extension Members in C# 14?

Extension members build upon traditional C# extension methods while eliminating key limitations. Instead of declaring individual extension methods with the this modifier, you create extension blocks using the new extension keyword to group related functionality.

Traditional Extension Methods vs Extension Members

Traditional extension methods in C# look like this:

public static class StringExtensions

{

public static int WordCount(this string str) =>

str.Split([' ', '.', '?'], StringSplitOptions.RemoveEmptyEntries).Length;

}With C# 14 extension members, the syntax changes:

public static class StringExtensions

{

extension(string str)

{

public int WordCount() =>

str.Split([' ', '.', '?'], StringSplitOptions.RemoveEmptyEntries).Length;

}

}The real power emerges from what you can now declare within extension blocks.

Extension Properties: Adding Computed Properties to Existing Types

One of the most valuable improvements is the ability to add properties to existing types. This C# 14 feature enables cleaner, more intuitive code:

public static class Enumerable

{

extension<TSource>(IEnumerable<TSource> source)

{

public bool IsEmpty => !source.Any();

}

}Now you can write expressive code that reads naturally:

var numbers = new[] { 1, 2, 3 };

if (numbers.IsEmpty) // Much more readable than !numbers.Any()

{

Console.WriteLine("No numbers found");

}Extension properties feel native to the original type, which is particularly valuable for domain-specific concepts where properties express intent more clearly than method calls.

Static Extension Members: Extending Types Beyond Instances

Traditional extension methods could only extend type instances. C# 14 extension members break this limitation by supporting static members, allowing you to add static properties and methods:

public static class PointExtensions

{

extension(Point)

{

public static Point Origin => Point.Empty;

}

}This C# extension feature enables code that feels completely native:

Point startingPoint = Point.Origin; // Clean and intuitiveStatic extension members are ideal for factory patterns, common constants, and utility methods that logically belong to a type but weren’t included in the original design.

Extension Operators: Adding Mathematical Operators to Any Type

Perhaps the most powerful C# 14 capability is extension operators. You can now add user-defined operators to types you don’t control, enabling natural mathematical operations.

Adding Arithmetic Operators to System.Drawing.Point

Let’s extend System.Drawing.Point with arithmetic operators:

public static class PointExtensions

{

extension(Point)

{

public static Point operator +(Point left, Point right) =>

new Point(left.X + right.X, left.Y + right.Y);

public static Point operator -(Point left, Point right) =>

new Point(left.X - right.X, left.Y - right.Y);

public static Point operator *(Point point, int scale) =>

new Point(point.X * scale, point.Y * scale);

}

}Your geometry code becomes beautifully readable:

Point p1 = new Point(5, 3);

Point p2 = new Point(2, 7);

Point sum = p1 + p2; // Point(7, 10)

Point difference = p2 - p1; // Point(-3, 4)

Point scaled = p1 * 3; // Point(15, 9)Using Tuples as Operands in Extension Operators

You can even use tuples as operands for more expressive C# operations:

extension(Point point)

{

public static Point operator +(Point point, (int dx, int dy) offset) =>

new Point(point.X + offset.dx, point.Y + offset.dy);

}

// Usage:

Point translated = myPoint + (5, -3);This approach dramatically improves code readability in domains involving mathematics, geometry, or any scenario where operators naturally express relationships between values.

Generic Extension Members with Type Constraints

Extension members work seamlessly with C# generics, allowing you to create specialized extensions for types meeting specific constraints:

public static class NumericEnumerableExtensions

{

extension<TElement>(IEnumerable<TElement>)

where TElement : INumber<TElement>

{

public static IEnumerable<TElement> operator +(

IEnumerable<TElement> first,

IEnumerable<TElement> second) => first.Concat(second);

}

}

//Usage:

var numbers1 = new[] { 1, 2, 3 };

var numbers2 = new[] { 4, 5, 6 };

foreach (var i in numbers1 + numbers2)

{

Console.WriteLine(i);

}This extension only applies when TElement implements INumber<TElement>, providing type-safe, specialized behavior for numeric sequences.

Understanding Receiver Parameters: Instance vs Static Extensions

Extension blocks distinguish between instance and static extensions through the receiver parameter. When you name the parameter, you create instance extensions that can access it:

extension(Point point) // Named parameter = instance extensions

{

public void Translate(int dx, int dy)

{

point.X += dx; // Can access 'point'

point.Y += dy;

}

}When you omit the parameter name, you can only declare static extensions:

extension(Point) // No name = static extensions only

{

public static Point Origin => Point.Empty;

// Error CS9303 : 'Translate': cannot declare instance members in an extension block with an unnamed receiver parameter

// public void Translate(int dx, int dy) { }

}This design keeps C# syntax clean while making developer intent explicit.

Performance Optimization: ref Extensions for Value Types

For value types, you can use ref, in, or ref readonly modifiers on the receiver parameter to avoid unnecessary copying and improve performance:

public static class AccountExtensions

{

extension(ref Account account)

{

public void Deposit(float amount)

{

account.balance += amount; // Modifies the original

}

}

}

public record struct Account(float Balance = 0);

//Usage:

var account = new Account();

account.Deposit(10);Without ref, the extension method would operate on a copy of the struct, losing your changes. This is crucial for performance when working with large value types in C#.

Migrating from Traditional Extension Methods to Extension Members

Both syntaxes coexist peacefully and compile to binary-compatible IL. You can migrate gradually from traditional C# extension methods:

Traditional syntax:

public static Vector2 ToVector(this Point point) => new(point.X, point.Y);Extension member syntax:

extension(Point point)

{

public Vector2 ToVector() =>

new Vector2(point.X, point.Y);

}The calling code remains identical in both cases. This compatibility means you can adopt C# 14 extension members at your own pace without breaking existing consumers.

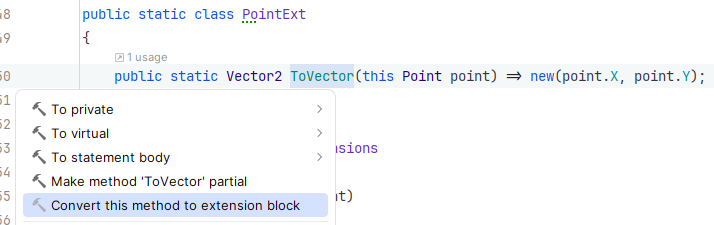

From Rider:

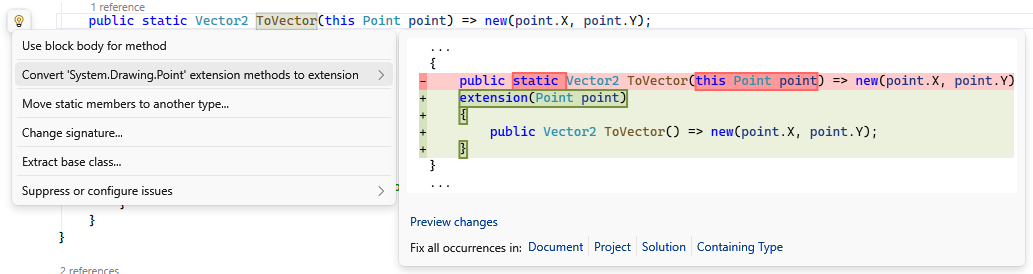

From Visual Studio:

Organizing C# Extensions with Extension Blocks

Extension blocks excel when you have multiple related extensions for the same type. Group them logically instead of scattering them across many methods:

public static class PointExtensions

{

extension(Point point)

{

public Vector2 ToVector() => new(point.X, point.Y);

public void Translate(int dx, int dy)

{

point.X += dx;

point.Y += dy;

}

public void Scale(int factor)

{

point.X *= factor;

point.Y *= factor;

}

}

extension(Point)

{

public static Point Origin => Point.Empty;

public static Point UnitX => new Point(1, 0);

public static Point UnitY => new Point(0, 1);

}

}This organization makes your C# code more maintainable and your intent clearer.

Real-World Example: Enhancing IEnumerable<T> Collections

Let’s build a practical C# extension that enhances IEnumerable<T> with both instance and static members:

public static class EnumerableExtensions

{

extension<TSource>(IEnumerable<TSource> source)

{

public bool IsEmpty => !source.Any();

public bool IsNotEmpty => source.Any();

public TSource? FirstOrDefault(TSource? defaultValue) =>

source.FirstOrDefault() ?? defaultValue;

}

extension<TSource>(IEnumerable<TSource>)

{

public static IEnumerable<TSource> Empty => [];

public static IEnumerable<TSource> operator +(

IEnumerable<TSource> first,

IEnumerable<TSource> second) => first.Concat(second);

}

}Usage becomes wonderfully expressive:

var numbers = new[] { 1, 2, 3 };

var moreNumbers = new[] { 4, 5, 6 };

if (numbers.IsNotEmpty)

{

var combined = numbers + moreNumbers; // [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

var withDefault = combined.FirstOrDefault(0);

}

var empty = IEnumerable<int>.Empty; // Type-level factoryC# Method Resolution: How Extension Members Are Resolved

Extension members follow the same resolution rules as traditional extension methods: they’re only considered when no instance member matches. Actual type members always take precedence:

public class MyClass

{

public void DoSomething() => Console.WriteLine("Instance method");

}

public static class MyClassExtensions

{

extension(MyClass obj)

{

public void DoSomething() => Console.WriteLine("Extension method");

}

}

var obj = new MyClass();

obj.DoSomething(); // Prints "Instance method"Extension members never override or shadow existing members—they only fill gaps in the API surface.

C# 14 Extension Member Limitations and Future Support

C# 14 focuses on methods, properties, and operators. Other member types—like fields, events, indexers, nested types, and constructors—aren’t supported yet, though they’re being considered for future C# versions. The current feature set already covers the most common scenarios and provides significant value.

Important Considerations for C# 14 Extension Members

Breaking Change Warning: If you have types or type aliases named “extension”, you’ll need to rename them. The extension keyword is now contextual and reserved for this C# feature (Error CS9306 : Types and aliases cannot be named ‘extension’).

Type Inference: For non-method members (properties and operators), all type parameters must be inferrable from the extension parameter. This keeps C# type inference predictable and avoids ambiguity.

When to Use C# Extension Members: Best Practices

Extension members excel in several scenarios:

Use C# extension members when:

- You want to add computed properties that represent state

- You need operators for types you don’t control

- You’re building domain-specific language features

- You want to add static factory methods or constants to existing types

- You have multiple related extensions for the same type

Stick with traditional extension methods when:

- You’re maintaining legacy codebases where migration isn’t justified

- You need simple, one-off extensions

- You want maximum compatibility with older C# versions at the source level

Conclusion: The Future of C# Type Extensions

Extension members represent a significant evolution in how developers extend and enhance types in C#. They enable more natural APIs, better code organization, and patterns that weren’t previously possible. The C# 14 feature integrates seamlessly with existing extension methods while opening doors to more expressive, domain-specific code.

As you explore C# 14 and .NET 10, consider how extension members might improve your APIs. Whether you’re building libraries, enhancing third-party types, or simply making your code more readable, this feature gives you powerful new tools for crafting better software.

Traditional C# extension methods aren’t going anywhere—they remain fully supported and continue to work exactly as before. Extension members simply give you more options, more expressiveness, and more ways to make your code communicate intent clearly. That’s the kind of evolution that makes C# such a joy to work with.

I’m curious—how does this topic show up in your own work or experience?